In March 2018, I sat in a crowded hallway outside an interview room at the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Office in San Francisco. Four Bay Area Cambodian refugees had been summoned to report to ICE, and I accompanied them with a few others. We waited with their families and lawyers as individuals were called in one by one.

We all stared at the door, waiting to see if someone would walk out of the room again. The Trump administration had been escalating deportations to Cambodia; I could feel the tension and fear in the air. I witnessed sighs of relief and hugs when one individual walked out and reunited with his family. I also saw devastated women weeping and young children crying when they were told their partner and father were taken into ICE custody.

Deportation separates families and has a lasting impact not only on the deported individuals but also on their loved ones. I’m at New Breath Foundation (NBF) because I want to help deportees and those at risk of being deported, specifically those impacted by both the criminal legal and deportation systems.

Who Is the Deportee Community?

Arun* is one of the thousands of Southeast Asian deportees affected by the prison-to-deportation pipeline. The US’s complicity in war, imperialism, and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Khmer, Vietnamese, and Laotian refugees is the precursor to how people like Arun end up in the pipeline.

Arun was a child when he and his refugee family fled their war-torn home country and made the arduous journey to the States. Resettling and adjusting to life in the US amidst trauma, loss, and violence was more than any child could or should have to bear. Like others, he endured racial slurs, bullying, and absent parents working to support their families. He, like others, found support and a sense of belonging in local gangs. He committed crimes and served time in prison.

After serving their time, some built new lives successfully upon re-entry. Many started families, formed their own businesses, or even joined the C-Suite at firms where they worked. But after the US and Cambodia signed a repatriation agreement in 2002, the US government began targeting formerly incarcerated Cambodian refugees like Arun. To this day, Cambodian refugees who have already served their time are at risk of deportation, family separation, and the uprooting of their lives simply because they have a record. And many, like Arun, have already been deported back to their home countries and are trying to make sense of their new reality.

The Listening Tour

I joined New Breath Foundation in 2019, the same year we led our first delegation to Cambodia. We called it the Listening Tour; our main goal was to meet with deported individuals and listen to their stories first-hand. We met with those who had recently arrived and those who had been in Cambodia for over 20 years. The stories were heartbreaking and often eerily similar.

“I’m here alone. My family at home are all dead.”

– Community member deported to Cambodia, 20 years ago

It really hurts to be separated from my kids and parents, a pain that never goes away. If the government could only put themselves in my shoes.

– Community member deported to Cambodia, ~12 years ago

After the Listening Tour, it became clear that the challenges and needs of folks impacted by deportation were vast and transnational. New Breath Foundation’s mission – to bring hope, healing, and new beginnings for folks harmed by unjust immigration and criminal justice systems – necessarily extends beyond the US borders. We formed a coalition called Kites to Cambodia. The group set up initial programs like CERI’s New Light Program (a tele-mental health program for deported community members in Cambodia) and APSC’s Care Packages Program, sending items to deported people throughout Southeast Asia. We supported the return of a few people to the US.

We continue to learn from the wisdom of those affected by the harmful systems of immigration and deportation and recognize the need for consistent commitment to our community overseas.

Building Community Amidst Isolation

Deported people are constantly punished for their past. They cannot rebuild their lives and contribute to society when the odds are stacked against them repeatedly.

Those who have been deported to Cambodia, in particular, face unique challenges. Whereas individuals deported to other Southeast Asian countries include those who overstayed their visas or entered the country undocumented, Cambodia is the only country where most deported from the US are formerly incarcerated. They face judgment from locals and discrimination from potential employers due to their status as formerly incarcerated deportees.

Last month, eight individuals from various partner organizations (New Breath Foundation (NBF), the Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC), the Center for Empowering Refugees and Immigrants (CERI), and Minnesota8 (MN8)) returned to Cambodia to meet with refugees who had been deported. Our coalition, renamed “Kites to Southeast Asia,” had several goals for this trip, some quite practical. But the most important goal was to let the deported community know we still care and haven’t forgotten about them.

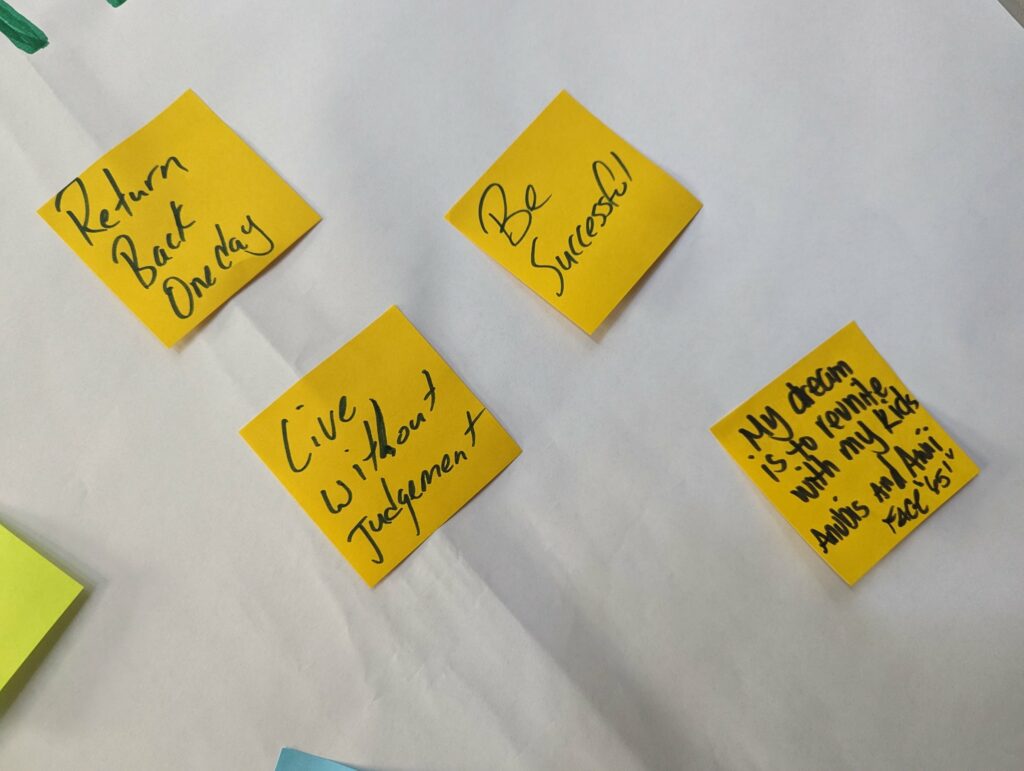

Over two weeks, we met one-on-one with individuals, ate meals together in smaller and larger groups, and created space for people to share their pain, challenges, and frustrations. We brought some of the things they missed from the US, such as Snickers bars, thick white socks, Crest whitening strips, Tylenol, and Combos (a pretzel snack with cheese filling).

We planned social events at businesses owned by deported folks in Phnom Penh and in Siem Reap. Many started their own restaurants serving pizzas, burritos, or burgers with “real American beef,” a connection to their past, or NGOs like Tiny Toones that “provides a safe and positive environment for [underserved] youth to channel their energy and creativity into the arts and education.”

During our trip, we identified several key themes, some we already were aware of and others that were new:

-

Not all deported people want to live in the United States again, but they do want to have the opportunity to visit their loved ones.

-

Some deported people do want to move back to reunite with their families and for an opportunity to earn a decent living.

-

Mental health support is critical. CERI’s telemental health program has made inroads with many people. Still, there’s limited capacity, and more resources are needed to serve more folks in Cambodia and other Southeast Asian countries.

-

Words and photos shared without consent significantly impact the livelihood of deported people. In the past, deported people have had their comments and pictures published without their review and approval. These actions negatively impacted their jobs because their workplaces didn’t know about their deportee status. In another instance, government officials contacted a deported individual regarding statements published in an article that he didn’t approve for publication.

During one of our sessions, we asked the group, “What message would you like to tell folks in the US?” One person responded with the following:

We are not dead.

We are still here.

We are still alive.

We are thriving for success.

We are still trying our best.

– Community member deported to Cambodia, ~20 years ago

I think about these sentences every day. These folks try their best to create a better life for themselves and their community, but their efforts and hopes are often unseen and unheard of.

Just the Beginning…

We continue to learn from and identify new ways to help those deported to Southeast Asia feel connected and remembered. At the end of our recent trip, we listed ideas like searching for additional mental health funding and supporting social events such as Thanksgiving or Christmas. But most importantly, we commit to returning every year to continue to support community and movement building.

We know this is just the beginning of our work with the deportee community. As we continue to provide hope and healing to Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) communities facing violence, incarceration, and deportation, we know this work must occur both here and abroad. To our friends in Southeast Asia:

You are seen.

You are heard.

You are remembered.

We will return.

We are going to continue to build together.

For more on Southeast Asian immigration and deportation:

-

The Devastating Impact of Deportation on Southeast Asian Americans from SEARAC

-

Decades After Resettling in America, Southeast Asians Continue to Fight for Basic Rights from Prism Report

-

Deported: Forced Family Separation from NBC Asian America

Resources from our partners on Southeast Asian immigration and deportation:

-

Resources for Southeast Asian Refugees Facing Deportation from Advancing Justice Asian Law Caucus (ALC)

-

Know Your Rights Resources in English, Khmer, Hmong, and Vietnamese from MN8

-

From Prison to ICE to Freedom: A Handbook for Immigrants Inside from ALC and APSC

-

Resource Guide for Southeast Asian Americans Facing Criminal Deportation from SEARAC

Ways to take action:

-

Pardon #APSC4! The APSC 4 – Borey “Peejay” Ai, Nghiep “Ke” Lam, Chanthon Bun, and Maria Legarda – are refugees and immigrants who have survived cycles of generational trauma and currently at risk of being deported. Find out more information at bit.ly/apsc.

-

Tiny Toones has made a huge difference in the lives of local underserved Khmer youth, but the organization is having a hard time securing funding. If you’re interested in supporting, you can make a donation at http://www.tinytoones.org/donate/ or contact them here.

*Name was changed to protect the individual’s privacy.

Stephanie Gee is the Director of Operations & Communications at New Breath Foundation. A daughter of Chinese immigrants, Stephanie is a San Francisco native who appreciates the challenges her parents and grandparents overcame to establish a life in the United States. She spent ten years working in online advertising sales and operations at Google. In 2016, Stephanie left the company and pivoted her career towards social impact work. She joined NBF in 2019 and has enjoyed the adventure of contributing to the organization’s rapid growth and working alongside an incredible team.