We sat down with NBF Board Member McArthur “Mac” Hoang, who joined the Board earlier this year and now serves on the NBF Fundraising Committee. We asked Mac about his relationship with NBF and experiences serving on the Board. We are in deep gratitude to Mac for his service and for sharing his reflections with us here.

Could you share a little about yourself and your journey?

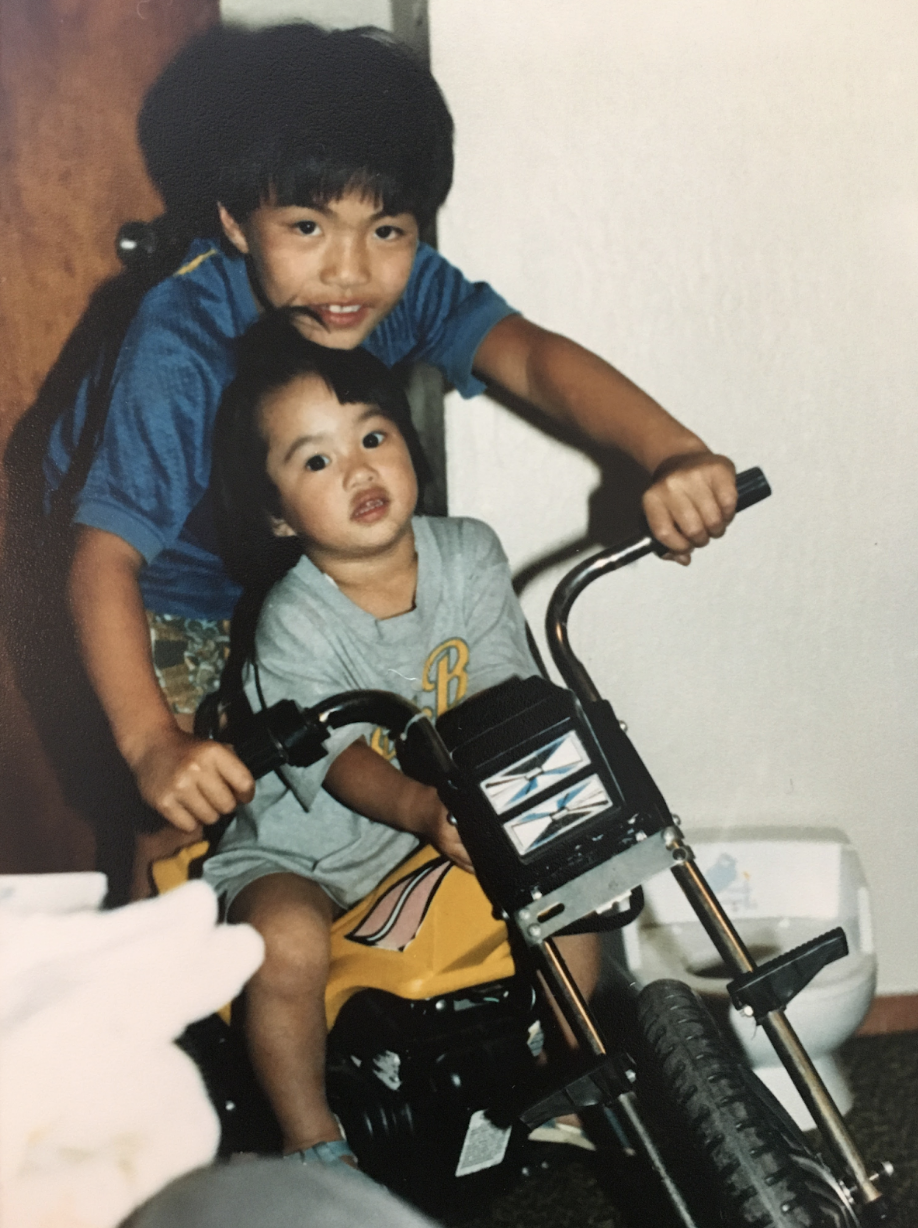

I come from a family of refugees from Vietnam. We dealt with the struggles of assimilation from a war-torn country. I’m the last of the wave that saw the overt brutality of racism. But there was also a unique undertone of racism I could see as a young child. My family was told to go back to our country and that we didn’t belong in America. I realized at a young age that there’s “us” and there’s “them.” These lived experiences were really important to me in understanding that, in America, our people are seen as “less than” and not “part of.”

I grew up during a time when the model minority myth was taking off. My family were refugees and not immigrants with high privilege; we were the poorest of the poor. Growing up, I witnessed the mental battles my father fought from his experiences with the war, which led to extreme violence in the household. Because of this, I watched how it affected my older brother as he started to act out. He began to become entangled in the criminal system. After his prison stay, he decided to sign the paperwork for deportation and removal. He currently lives his life in America in limbo—holding his breath—waiting for the moment that Vietnam accepts deportees like him. I made a conscious decision as a young child not to get too close to my brother, knowing that I could lose him at any moment to deportation. I would follow my brother into that lifestyle.

How did you first learn about NBF?

I was around before NBF was a thing. I know Eddy from the ‘90s when we were both incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison. “Lifer Eddy,” as he was called, doesn’t remember me from that time. I’m just one of thousands of people that moved through that prison. I was doing what we call “life on an installment plan,” going in and out of prison with violations and new charges, over and over—fighting my addictions.

Back then, I think the governor was releasing 1, 2, or maybe 5 lifers upon completion of their tenure as governor. I remember the glassy look in Eddy’s eyes, the look of hopelessness. We couldn’t get to know him with that shell that he created, that other lifers created. A lot of us short-timers took heed, not to mention when we were going home because a lot of them weren’t going home or didn’t think they were going home. That look is to protect them against guys like me—I was a citizen, and there was no fear of deportation. But my brother, Eddy, and the rest of them had to sit in the unknown and endure.

Eddy and I would be the first to admit—we weren’t the smartest guys in there. We just had the luck to get a chance—a chance at freedom, a chance at redemption, and a chance to help the next generation. I went on to find treatment to fight off my addictions. I re-entered higher education with the goal of helping the formerly incarcerated find the pathway to higher education and meaningful employment. I graduated from UC Berkeley with honors and as the Chancellor’s Award recipient. Along the way, I was able to raise millions to support vulnerable populations and help thousands of people change their life trajectories. It took a bit of luck and opportunity for me to find success. There were times when, if the right opportunity didn’t present itself, I would have to drop out of school and face the reality of homelessness. What if we gave others similar opportunities and took away chances? That’s what NBF does. NBF supports organizations that give AANHPIs hope, support, and opportunities.

Why do you believe in the work that NBF is doing? What drives you to serve on the Board?

As a Board Member, I have a passion for changing philanthropy for the AANHPI community. The model minority myth often creates a society in which America believes that the AANHPI population does not need support. AANHPIs have some of the highest incarceration and deportation rates per capita in America. We have unknown high levels of mental health disparities that need to be addressed. I want to bring AANHPI issues to the forefront of the social conscience of society. The underfunding of AANHPI organizations showcases society’s belief in the model myth minority and reinstates to our people that we are less than and not a part of.

Being “other-ized”—or perceived that “those immigrants don’t need help”—drives me to be on the NBF Board. If you look at my Vietnamese upbringing and look at the numbers in San Jose, where I’m from, the high school diploma rate for the Vietnamese community is extremely low. Employment outcomes are lower than other groups. Yet it is a widely unknown issue. There’s an undertone of racism that plays a key role in the philanthropy sector, knowing that support for AANHPI communities is the lowest of all groups. For every hundred dollars spent, AANHPI organizations get pennies, less than 2%. At this point, we are an afterthought, and the truth of the matter is that our people need help.

Do you ever feel pressure to fight this fight as one of the few with lived experience?

Pressure would be one feeling, yes. But a sense of duty and honor would be a secondary feeling. Being a person with lived experiences in these spaces sometimes is exhausting, having to explain yourself and educate the masses. But there’s another view, historically speaking, of the carceral state we live in, inequalities in society, and “the haves” versus “the have-nots.” With this perspective, you have to do something because the system won’t change by itself. So, considering how slow things change, there’s no pressure of, like, “Oh, I might mess this up.” Nothing will change unless we voice it. So, for me, I’ve gained this perspective that I might as well push, shove, kick, and scream versus stay quiet.

There’s an undertone in the API community of being a good immigrant and shutting up. And shutting up hasn’t gotten us far. That’s a memory I have of my family, a bunch of non-English-speaking refugees just shutting up, staying quiet. And it didn’t help us. And maybe that’s a burn that’s in me that drives me today. I refuse to be the quiet Asian. Not to say there’s nothing wrong with being quiet—and I should learn more from my culture to be quiet—but I think we, as a unit, should be more outspoken. If I have to be the tip of that spear, so be it.

Can you share how your lived experience informs your work as an NBF Board Member and Reentry Manager at APSC?

Before I was the Reentry Manager at the Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC), I was supported by APSC, and I needed every bit of that support—financially and emotionally when coming home and during my educational journey. APSC helped me re-enter society, gave me a safe space to practice societal norms, and gave me a community of men to learn better skills for being a father and a new grandfather. Now, I have a beautiful relationship with my daughter and am able to be present in my granddaughter’s life. The fact that I am able to maintain an open relationship with my loved ones showcases the importance of the work that our NBF grantees do to keep families together—I’ve experienced the positives of NBF’s work firsthand. So, part of what motivates me to be on the Board is to give back.

If we want change, we must understand how critical change happens. We must infuse new ideas and thought partners into organizational missions to shift the paradigm. Infusing people like me with different viewpoints creates a paradigm shift. People with lived experiences can remove blind spots, bring new visions, and add new perspectives to organizations. Those perspectives count. For example, I’m a reader of grant proposals at NBF. I am able to give critical insight during our meetings that enriches the conversation and expedites the process for change.

My experience on NBF’s board and working at APSC has been fantastic; the most rewarding positions I have ever had. I feel like I’m riding a unicorn at APSC and NBF. We are trailblazing where others have not gone. There are only a handful of organizations that fight for AANHPI communities that have dealt with incarceration, deportation, and detentions—the plight of the refugees. Our population, as small as it is, still needs support. And that’s what we’re pushing for at NBF, to push the pendulum in the philanthropy world. It’s long overdue for the world to reimagine philanthropy where the AANHPI community is included.

—

McArthur Hoang, the youngest of 10, is the only child born in America from a Vietnamese refugee family. His family fled from Vietnam, landing by boat in the Philippines, and was granted political asylum. The Vietnam War had devastating effects on the Hoang family. Mac grew up in socially toxic environments that exposed him to life-altering trauma. Mac has lived experience, intersectionality, and the inter imbrication of adverse childhood experiences, disability, addiction, foster care, and carcerality more broadly. Mac has been intertwined with systems since he was a young child—most recently, Mac was released from prison in 2014, where he began to rebuild his life with the foundation of sobriety. Mac graduated with honors from the Sociology Department at UC Berkeley in 2020. Mac is the Reentry Manager at APSC, supporting those reentering society from institutions. Because of his past experiences, Mac’s calling is to be of service to the community. His passions lie in supporting formerly incarcerated, foster youth, and disabled persons to find meaningful employment and improved life outcomes.