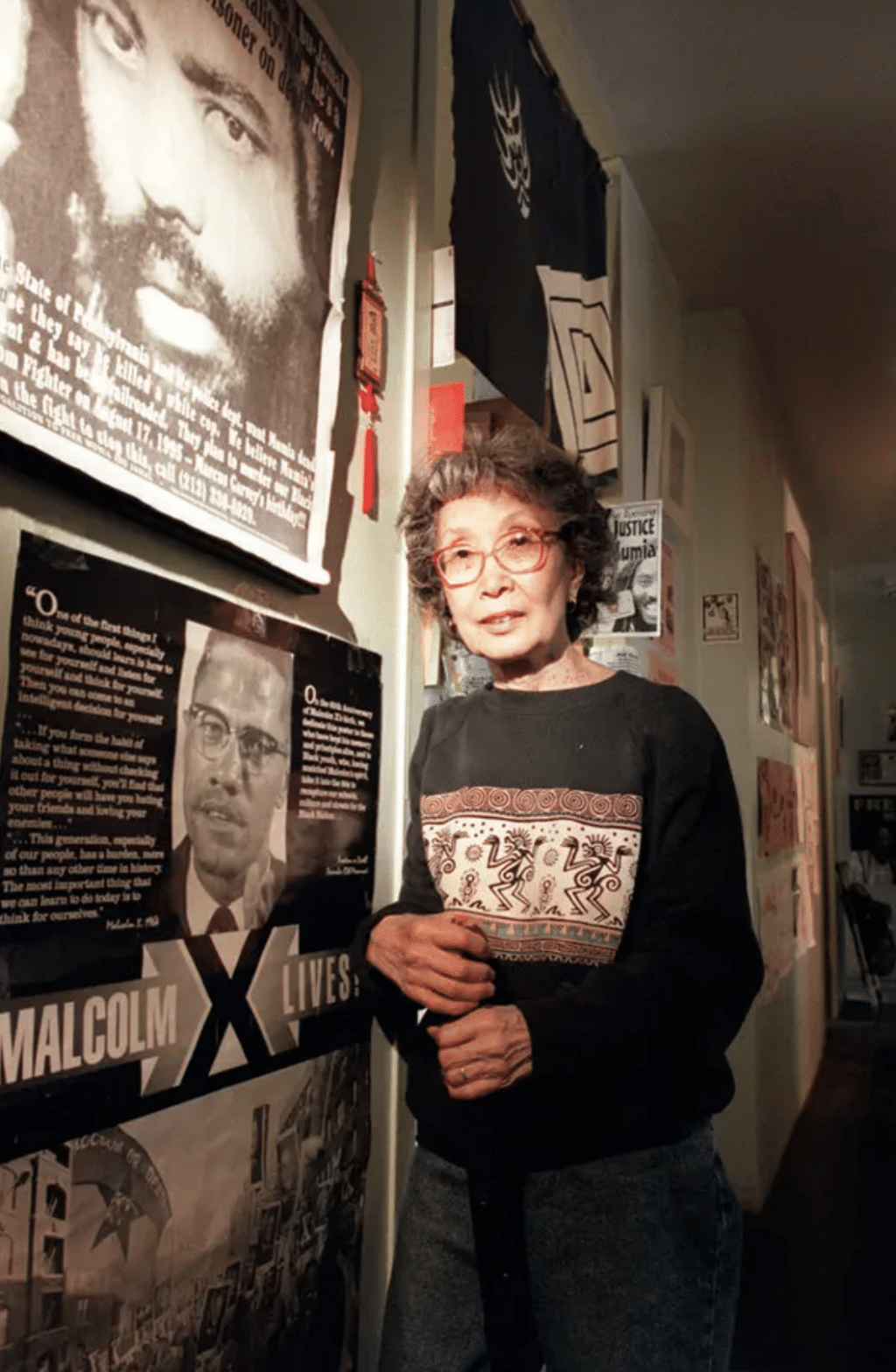

“True liberation comes from recognizing and embracing our interconnectedness.”

-Yuri Kochiyama

February is significant not only because we celebrate Black History Month, but also because we join countries around the world in celebrating the Lunar New Year. I can’t think of a better time to reflect on the importance of racial solidarity than on the heels of the annual joint Black History Month and Lunar New Year celebration, which has taken place in Bayview Hunters Point, San Francisco, for the last 14 years in a row. Every year, New Breath Foundation (NBF) sponsors the event because it brings the Black and Asian communities together.

As we enter the Year of the Dragon, I want to lay out a framework for our work at NBF. We are living into three main values—Collective Learning, Collective Healing, and Collective Liberation—which we will focus on in subsequent blog posts. However, the through line of these three values, what binds them all together, is racial solidarity. Without racial solidarity, there can be no collective liberation.

What do I mean by racial solidarity? I want to share some examples of events and organizations that encapsulate this work, focusing on three key points:

- Racial solidarity requires regular, safe spaces for connection and learning about our culture, history, and identity (CHI).

- Racial solidarity requires endurance, long-term commitment, and relationship-building.

- Racial solidarity requires recognizing the disproportionate impact of systemic injustice on communities of color.

1. Racial solidarity requires regular, safe spaces for connection and learning about our culture, history, and identity (CHI).

The Bayview event illustrates the importance of creating spaces for community members to feel safe interacting with each other. Historically, the Bayview-Hunters Point districts had a large Black population; Bayview-Hunters Point’s economy largely depended on the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard from World War II, which drew African-Americans to settle in the area for dockyard jobs. In the early 2000s, a lot of Asian immigrants started moving into the Bayview area, causing tensions between the Black and Asian communities; Census figures showed the percentage of African-Americans in Bayview declined from 48% in 2000 to 33.7% in 2010, while the percentage of Asians increased from 24% to 30.7%.

Things came to a head in 2010 when there were increased incidents of violence or bullying of Asian elders in the Bayview district. There was a lot of fear, mistrust, and blame placed on whole communities. The language barrier and cultural differences made it very difficult to communicate and build bridges. Gina Fromer, former Executive Director of Bayview YMCA, and Julianna Choy Sommer, former Board Chair, decided we needed to come together and create spaces for cross-cultural engagement. Since I was working at the Community Youth Center of San Francisco at the time, the collaboration was aligned. This annual celebration was one such event, and I’m proud to say that this effort has continued to this day.

When we create these types of safe, shared spaces, we carry the mindset that doing so will allow us to better understand each other’s culture, history, and identity, or CHI. These spaces create opportunities for consistent, ongoing engagement with one another. Then we are less likely to do harm and more likely to advocate for each other and see how we are connected in multiple ways as we survive and live alongside one another.

New Breath Foundation partners with several grantees who work directly on issues of racial solidarity. One example is the Yuri Kochiyama Solidarity Project, which works to carry on Yuri’s passion for justice and her lifelong commitment to connecting people, communities, and organizations to each other in solidarity. The Kochiyama family and others who work with the project create spaces at schools and through teach-ins, art projects, and events for people to learn about their history and culture and ultimately to demonstrate the importance of racial solidarity. Their work carries on the legacy of Yuri, Malcolm, and others who believe in the importance of solidarity among BIPOC communities.

2. Racial solidarity requires endurance, long-term commitment, and relationship-building.

To do effective racial solidarity work, we must be willing to make a long-term investment, not just sporadic efforts here and there. People will start something, and when the event is over, they go about their business. Then there’s no more engagement until another thing happens. As my co-organizer, Tacing Parker, Senior Executive Director of Bayview Hunters Point YMCA, said, “It can’t just be an event, right? It takes the long haul to really be able to effect the change that’s needed.”

For the Bayview event, Black and Asian communities made a commitment to each other, acknowledging the value of cross-cultural engagement and learning. We want to replace the norm of violence with the norm of celebration and unity. So that’s why we consistently work on it, create spaces for it, so that people recognize that there are good things happening in our community and that there are people who actually want to learn about each other’s CHI. We continue to build with each other throughout the year: the event co-organizers and I are in regular communication with each other and have shared values that we stand on. We respect each other’s input and ideas, because we have built trust over many years.

Many of our grantees, in their communities and regions, practice racial solidarity and cross-cultural engagement based on critical analysis and lived experience of how systemic racism has impacted POC communities. SEAC Village is one example. SEAC Village is a grassroots-led social justice organization serving Southeast Asian and Black communities in North Carolina, primarily Guilford, Wake, Catawba, and Mecklenburg County. SEAC Village has largely organized around police violence and Southeast Asian deportation since 2012. They focus on contextualizing and interrogating the history and systems that affect refugee, Black, and immigrant communities to understand the root causes of oppression and violence and form the foundation on which to build a long-lasting and intersectional movement.

SEAC leaders co-organize with the Black community. For example, during the Charlotte uprising in 2020, organizers protested together, demanded justice, supported people who were arrested and advocated for their release and bail, working for Black and queer folks. In turn, Black staff on their team are learning about the incarceration and deportation of Southeast Asians in their community. They understand that the issues are intricately connected among their communities and are living out strategies for multiracial coalition building and mutual aid work.

3. Racial solidarity requires recognizing the disproportionate impact of systemic injustice on communities of color.

As we acknowledge and uphold Black History Month, and as Asian communities worldwide continue to celebrate Lunar New Year, we encourage our readers to continue in the ongoing work of racial solidarity beyond this month. Our duty and responsibility, especially those of us in the AANHPI community, is to understand and advocate for the Black community, with the acknowledgment that Black people regularly and systematically experience racism and targeting based on the color of their skin. As AANHPI living in the US, we recognize that systemic racism primarily targets Black bodies. Even though we are discriminated against as AANHPI, the likelihood of being targeted at the same level is different. If we understand systemic racism and white supremacy, then we have the responsibility to fight not just for ourselves but for other communities.

This does not mean we stop advocating for ourselves. NBF exists primarily to support AANHPI who are impacted by immigration, incarceration, deportation, and violence. At the same time, we know that collective liberation can only come with racial solidarity. We all need to continue to build bridges, build trust, and fight not just for individual liberation but collective liberation.

Let’s continue to celebrate our unity and focus our efforts on coming together and learning more about each other. We at NBF are in it for the long haul and invite you to join us in this fight—until we are all free.